What am I getting myself into?

Several years ago (well, in 1992) I programmed a Tetris clone on my Commodore 64 using assembler and several floppy disks. The D64 file can be found on CSDB if you want to try it! My good buddy Soft Ice created the music and sound effects. It’s still a nice version, if I do say so myself, even if it does have a few problems with timing and control.

Animation of the 1992 original title screen attract mode

Animation of the 1992 original title screen attract mode

I still have the source code to this game and it’s been really fun to read it, although it is obvious I was not a really good programmer in those days. I thought it would be fun to try to re-program the game using today’s cross-platform tools and my infinite game development skills and wisdom gathered in the years since 1992. :)

The plan is to re-use the graphics and music and sound effects from the old 1992 version, but totally reprogram the game itself.

I am not going to explain 6502 programming from the ground up in full in these series, and I will assume you know a bit already about assembly and the Commodore. I will document how I will try to recreate the Tetris game for the Commodore 64. A lot will become clear as more and more code is added, and I will try to be really detailed in the source comments.

Tip

If you do have questions about the code, do not hesitate to ask!!

This code should run on any 6502 based machine, provided the machine specific features (screen memory, audio and video chip addresses etc) are modified to suit the destination system.

Development setup

Here is what I am using:

- Kick Assembler

- Sublime Text

- VICE C64 Emulator

I will introduce more tools as we go along as I am not sure entirely what I will need in the future although some graphics tools for editing the character sets and game screens will be needed.

Graphics Approach

Tetris lends itself beautifully for a text based approach for the graphics. Blocks can be printed and moved about using characters. We will be manipulating the screen memory directly to print and modify the blocks, but we will also be using some of the KERNAL routines.

Stage 1: Blocks!

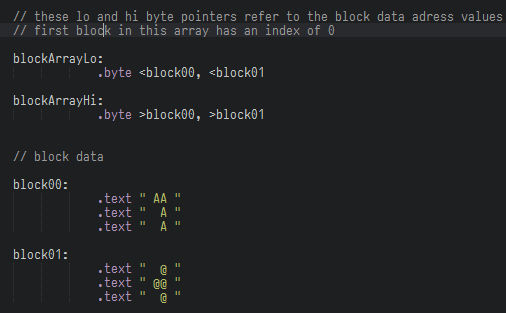

The first thing to do is to get blocks on the screen. I choose to define blocks of text data representing the well known Tetris shapes. The block data will be retrievable by passing an index to a function. For this we will need a table pointing to the block data. Here is how that does look in source code:

The blockArrayLo and blockArrayHi bytes point to the actual addresses where the block data is stored, seen below. These array values we will use in the draw block function coming up later.

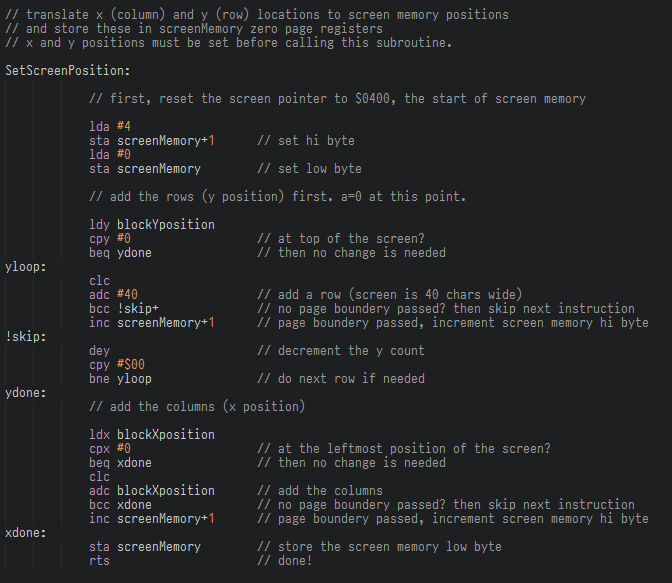

Now, how to get this on the screen? This is a two stage process. We will put these values straight into the Commodore 64 screen memory, so first we need a function to locate the memory location corresponding with the x and y coordinates of the block. The Commodore 64 screen memory is located at $0400 to $07f0, with $0400 being the top left position on the screen. As the screen is 40 characters wide I came up with this code:

The screen memory spans several memory pages ($04 to $07) so the page boundary check is there to up the hi byte of the address if we cross a page boundary. The check uses the carry bit to see if the lo byte has rolled over from $ff to $00. The screenMemory address is a zero page address defined as:

This zero page address now points to a screen memory position where we will print the block. We will be using zero page indexed with y addressing to get to this. Next step is the print function:

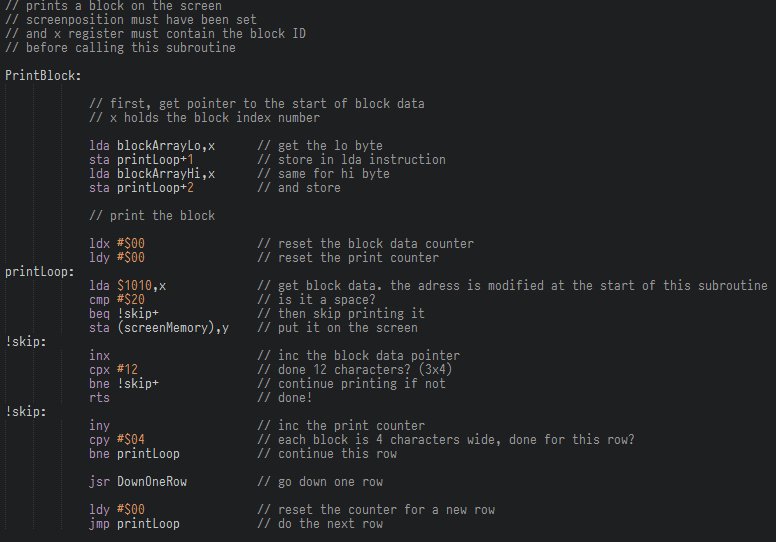

This code also introduces a extremely powerful and dangerous machine code programming technique: self modifying code. The first statements in this subroutine alter the code at the label printLoop: the LDA function is modified to point to the block data address, so we can later read this without fiddling with x and y registers. If we had used zero paged indexed with y addressing for reading the block data as well as the screen memory address, we would have to juggle the Y register around while reading and printing which would just be messy and unnecessary complex.

We do not print spaces as we could over write parts of other blocks already on the screen.

The STA(screenMemory),y statement puts the data on the screen, as this zero page address points to the screen memory adres we earlier determined using x and y coordinates.

Block data is 3x4=12 characters in length which is used to check if we are done yes or no, and each block is 4 characters wide so we check that to determine if we need to go one row down while still not being done drawing the block.

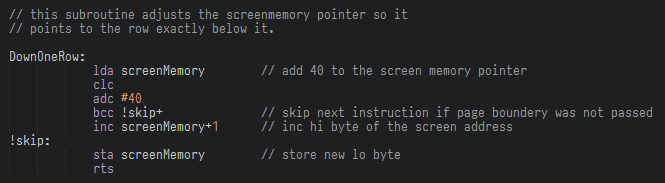

The DownOneRow function simply modifies the zero page pointer one row down:

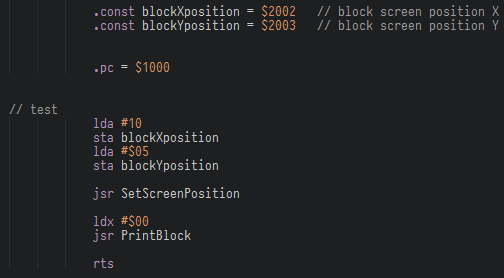

I’ve put this in a separate subroutine because I have a feeling that this bit of code will be used a few more times. We are nearly there, and with a little test program we can print a block on the screen:

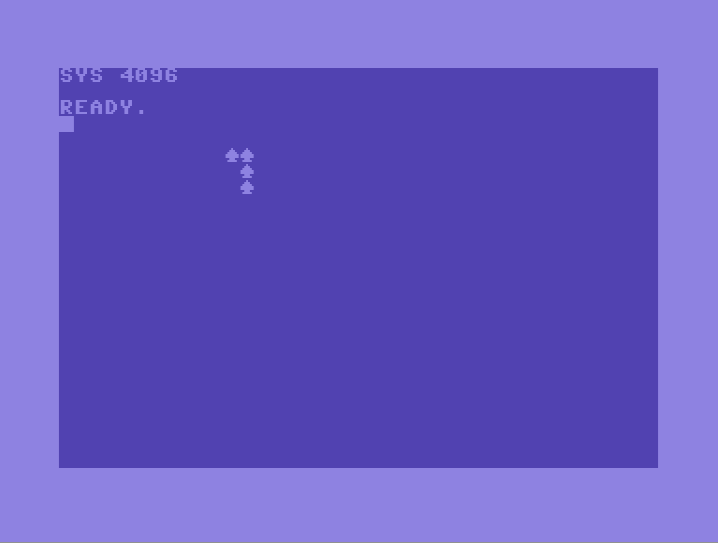

This test should print a block on the screen as position 10,5. The printed block will be the block with index 0:

Excellent! Next up will be adding more block shapes, and being to able to rotate them. This should not be too hard, as the code written is flexible. Passing coordinates and an index is all we need to get to the block we need.

Concluding

As you have noticed, machine code programming is an exersise in procedural logic and knowing how to modify the machine you are programming on. It’s also fun! No API’s to learn, and nothing between you and the machine.

The next part is here: Tetris in 6502 - Part 2.