Hi there and welcome to part 4. This is turning into a fun series, I am quite enjoying myself here.

Let’s address some things before we move on:

The code I am writing can be found on GitHub. If you use Kick Assembler as well you should be able to compile this code as is. You will need slight alterations if you use another assembler.

If you look at the repository you will see that I have split the code up in multiple files. There is a block file, a screen file, etc. It helps to keep track of the code by categorising it. The files starting with test_ contain small setup code and a loop to test specific code parts.

Also, I intend to write a post about code optimisation once the game is complete. I’m sure there are lots of ways to make this code go faster or make it shorter. I would be happy to hear about the code or the used algorithms, so just write a comment when you feel you can help me out.

Let’s start!

So far we’ve got a playing field, and we can move our block around. This is great, but there is no collision checking and so the block can move through our scenery, which is not so great.

Block Collisions

Now to get collision working. What do we need? When we move the block, we must not move into screen data that is already there. That other screen data is either the ‘wall’, or a previously dropped block. We will tackle this by implementing a new subroutine which will check if there is sufficient space where we want to print the moved block.

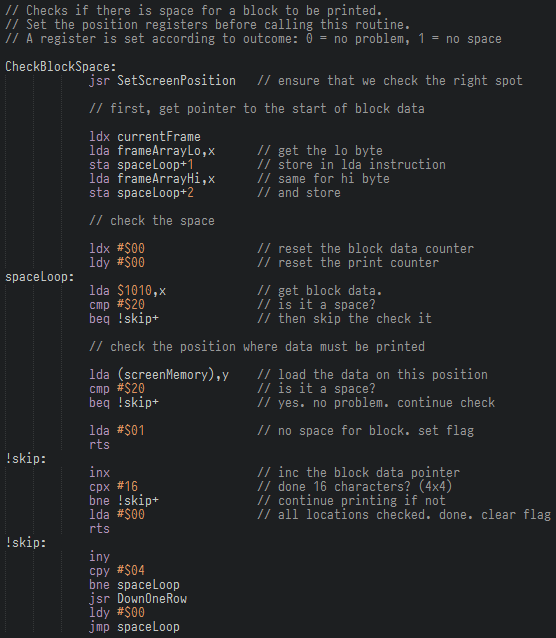

We should be able to use a variation of the EraseBlock subroutine. I called it CheckBlockSpace:

We could also have added this to the print routine itself, but it would get too messy, with removing, checking, printing, not printing, moving back to the old position. Well you get the idea.

The above code checks the space where the block should be moved to (printed at) and it will set the A register to 0 if there was no overlap with screen data, or it will set A to 1 if there was overlap, meaning a collision.

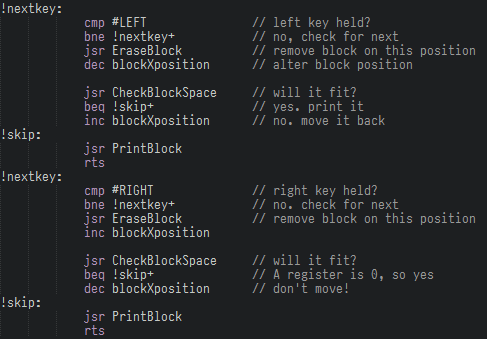

We can then act upon this in the input sub routine:

This is just a part of the input routine, but it’s about the same for all movement keys: erase block from the current position, update the position, check the new position, print if block fits, move position back and print if not.

We now can move left and right, but we cannot penetrate other screen data (meaning the wall or earlier dropped blocks) Also, all frames of a block are supported automatically. But a block on the top does not make a Tetris game. So let’s move on to:

Falling Down

The procedure for falling down is easy: count down a delay timer, adjust the block Y position, check if we can move there; if not, leave the block on the screen and create a new block. This way, it will lay on top of whatever was underneath it and it is automatically collision check material. Nice.

To make the countdown delay work, we need some timing code. Our code currently runs as fast as it can, which will result in erratic behaviour. One way to time our code is use the raster. For all you new people around here (meaning: not used a CRT monitor for all your life) : The raster is the beam that builds up a display. The raster of the Commodore 64 moves from the top of the display to the bottom of the display and then restarts at the top.

Here is an excellent explanation of the mechanics of the raster.

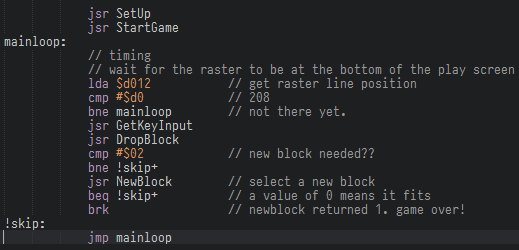

We can time code to run at a certain raster position. For this we use the magic memory location $d012. When this location is read, the current position of the beam is returned. So we add this to the game main loop:

We check the value of $d012 and keep doing that until it hits position #$d0. This is right below the screen data, at row 22. Running our code here means that any screen manipulation we perform will not result in flicker, AND the code will only run once per frame. This is another enhancement from the old version which flickered occasionally.

[!Note:] You might have noticed that I have rearranged the main loop a bit, with dedicated Setup and StartGame calls. We’ll keep reordering the main loop until we have a complete game.

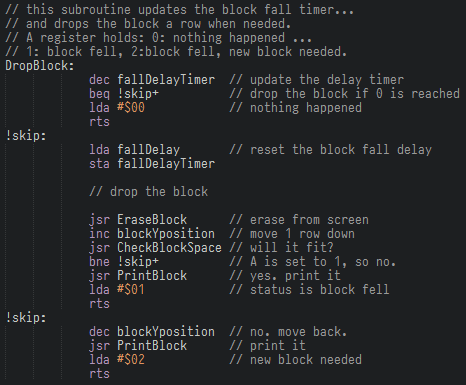

So, the code is run when the beam hits position #$d0. Player input is checked and after that the block is dropped one row down. That code is as follows:

Ah finally, here is that fall down counter. It gets changed until its value is 0. Then we drop the block down one row. And here is another essential part of the game: will the block fit on that new position? If not, then move it back, leave it there, and create a new block. The exit status determines the action we take when returning from this subroutine.

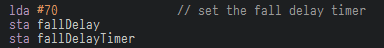

The setup subroutine also includes this code:

70 updates is the current fall delay. This means that a block falls each 1.2 seconds. Sounded like a nice slow start to me.

The main loop code checks if the returned value is #$02. If it is, a new block is needed. If that new block does not fit (eg: overlaps any dropped block) then it’s game over. The BRK instruction will exit the game for now.

How to check if the block has reached the bottom of the well? Easy. We add a row of an empty character (but not #$20 (space) ) at the bottom of the play field so the bottom of the well is sealed. This way we do not need to check for the Y position of the block to detect whether it is at the bottom. The collision detection is enough. I love cheating.

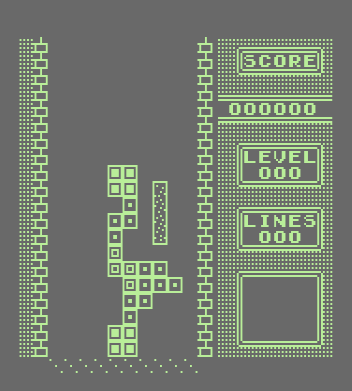

I added one row to the play field, and put in some characters there. I will remove the dots later on, but so far so good:

Our block falls down, and when it is placed, a new one is created, and the well is slowly being filled up.

Concluding

Getting the timing right is important for every game, from old 8 bit systems to the latest blockbusters… See what I did there? :)

Anyway, as some of you might have noticed by now: the game will run faster on NTSC (60 hz) machines. Linking your timing code to screen display updates does that for you. There are ways around that, but let’s not over complicate things for now.

We nearly have a working Tetris game! The next part will handle line checks, and moving the remaining screen data down. This might get tricky :)

See you next time. Happy coding! The next part is called Tetris in 6502 - Part 5